td;dr

Look! A flashy demo with buttons!

Background

A long time ago, we were investigating a way to expose text-to-speech functionality on the web. This was long before the Web Speech API was drafted, and it wasn’t yet clear what this kind of feature would look like. Alon Zakai stepped up, and proposed porting eSpeak to Javascript with Emscripten. This was a provocative idea: was our platform powerful enough to support speech synthesis purely in JS? Alon got back a few days later with a working demo, the answer was “yes”.

While the speak.js port was very impressive, it didn’t answer many of our practical needs. For example, the latency was not good enough for making a responsive UI, you could wait more than a couple of seconds to hear a short phrase. In addition, the longer the text you wanted to synthesize, the longer you needed to wait.

It proved a concept, but there were missing pieces we didn’t have four years ago. Today, we live in the future of 2011, and things that were theoretical then, are possible now (in the future).

asm.js

Today, Emscripten will compile C/C++ code into a subset of Javascript called asm.js. This subset is optimized on all current browsers, and allows performance to be about 2x native. That is really good. eSpeak is a pretty lightweight library already, the extra performance boost of asm.js makes speech instantaneous.

Transferable Objects

Passing data between a web worker and a parent process used to mean a lot of copying, since the worker doesn’t share memory with the parent process. But today, you can transfer ownership of ArrayBuffers with zero copying. When the web worker is ready to send audio data back to the calling process, it could do so while maintaining a single copy of the audio buffer.

Web Audio API

We have a slick, full featured Audio API today on the web. When speak.js came out in 2011, it used a prefixed method on an <audio> element to write PCM data to. Today, we have a proper API that enables us to take the audio data and send it through an elaborate pipeline of filters and mixers, or even send it into the ether with WebRTC.

Emscripten Got Fancy

This was my first time playing with it, so I am not sure what was available in 2011. But, if I have to guess, it was not as powerful and fun to work with. Emscripten’s new WebIDL support makes adding bindings extremely easy. You still get a chance to do some pointer arithmetic, but that’s supposed to be fun. Right?

So here is eSpeak.js!

I wanted to do a real API port, as opposed to simply porting a command line program that takes input and writes a WAV file. Why? two main reasons:

- eSpeak can progressively synthesize speech. If you provide a callback to espeak_Synth(), it will be called repeatedly with as many samples as you defined in the buffer size. It doesn’t matter how long the text is that you want synthesized, it will fill the buffer and return it to you immediately. This allows for a consistent low latency from the moment you call espeak_Synth(), until you could start playing audio.

- eSpeak supports events. If you use a callback, you get access to a list of events that provide a timestamp in the audio, and the type of event that occurs there, such as word or sentence boundaries.

And, of course, with all the recent-ish platform improvements above, I was really time for a fresh attempt.

Future Work

- Break up the data files. Right now, eSpeak.js is over a 2MB download. That’s because I packaged all the eSpeak data files indiscriminately. There may be a few bits that are redundant. On the flip side you get all 99 voice/language combinations (that’s a good deal for 2MB, eh?). It would be cool to break it up to a few data files and allow the developer to choose which voices to bundle or, even better, just grab them on demand.

- Make a demo of the speech events. It makes my head hurt to think about how to do something compelling. But it is a neat feature that should somehow be shown.

- ScriptProcessorNode is apparently deprecated. This is going to need to be ported to an AudioWorker once that is widely implemented.

I’m done apologizing, here is the demo.

The Internet is a global public resource that must remain open and accessible.

Mozilla invests in accessibility, because it’s the right thing to do.

We have staff, a team of engineers, who exclusively focus on accessibility in our products and play a positive influence in the general accessibility of the web. This has paid off well, Firefox is well regarded as a leader in screen reader support on the desktop and on Android. We have the best HTML5 accessibility support in our browser, and we are close to having a fully functional screen reader in Firefox OS.

I say “close”, because we are not yet there. Most websites are fairly accessible with little to no effort from the site developers. The document model of the web is relatively simple and is malleable enough that blind users are able to access them through screen readers. Advanced web applications are a whole other story, developers are required to be much more mindful about how they are authored and account for users with disabilities when designing them. The most recognized standard for making accessible rich internet application is called ARIA (accessible rich internet applications), and it allows augmenting markup with attributes that will help assistive technologies (such as screen readers) have a good understanding of the state of the app, and relay it to the user.

In Firefox OS we have a suite of core apps called Gaia that is the foundation for Firefox OS’s user interface. It is really one giant web app, perhaps one of the biggest out there. Since our mission dictates that we make our products accessible, we have embarked on that journey, we created a screen reader for Firefox OS, and we got to work in making Gaia screen-reader friendly. It has been a long and sisyphean process, where we would arrive at one module in gaia, learn the code, fix some issues, and move on to the next module. It feels something like this:

A California Department of Forestry helicopter dumps water on a grass fire in Benicia. (Robinson Kuntz/Daily Republic)

A California Department of Forestry helicopter dumps water on a grass fire in Benicia. (Robinson Kuntz/Daily Republic)

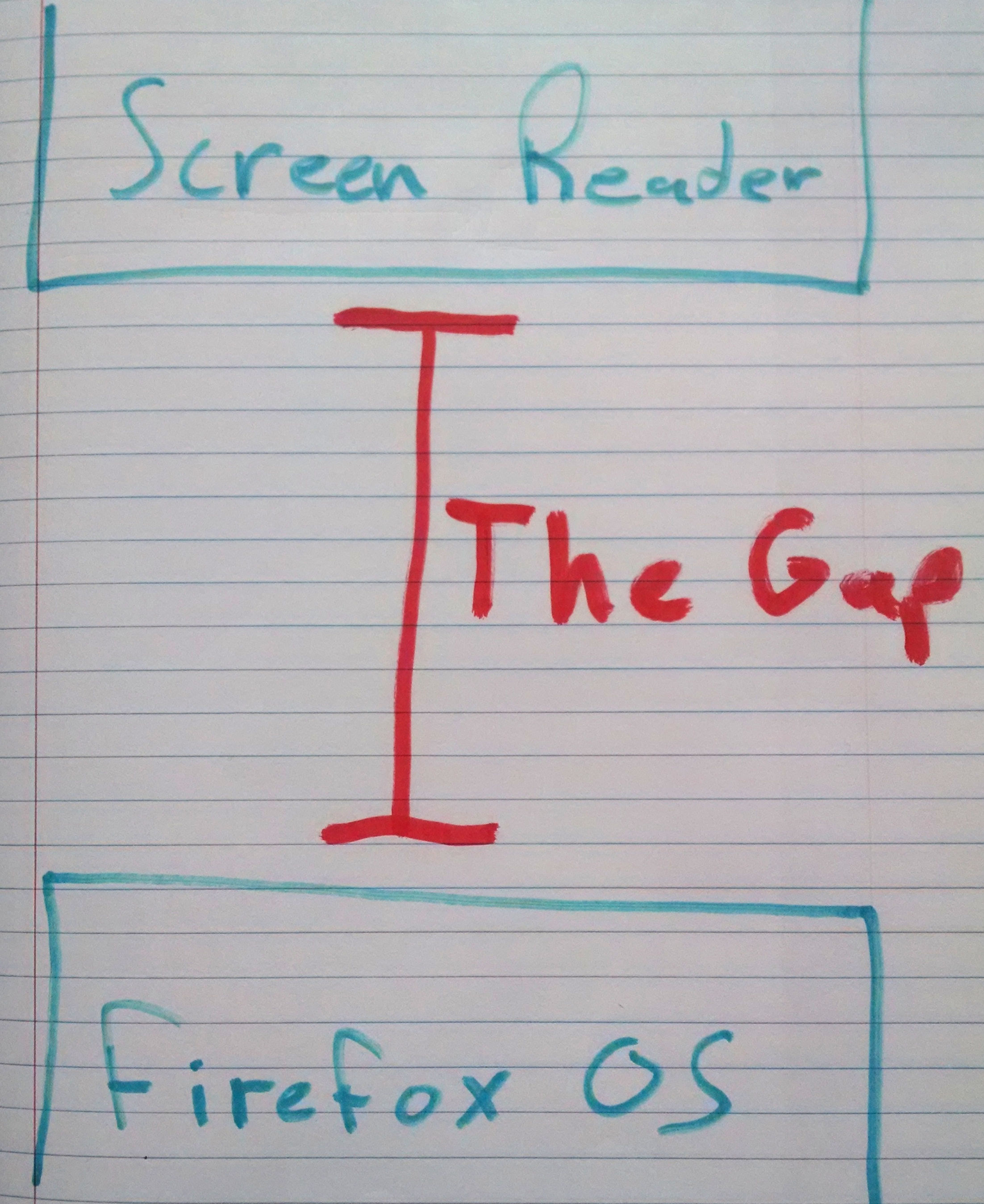

Firefox OS has grown tremendously in a couple of years. Things never slowed down, and we were always revamping one app or another, trying out something new, and evolving rapidly. This means that accessibility was always one step behind. If we got an app accessible in version n, n+1 was around the corner with a whole new everything. Besides working on Gaia, we have always been looping back to our screen reader, making it more robust and adding features. We have consistently been straddling the gap:

Firefox OS has achieved some amazing milestones in its short life. Early in the project, there was still a hushed uncertainty. Did we over promise? Could we turn a proof of concept into a mass-market device? There were so many moving parts for a version one release. Accessibility was not a product priority.

The return on investment

When I think about making our products accessible for the people that can’t see or to help a kid with autism, I don’t think about a bloody ROI.

Take 5 seconds, and let that sink in. Apple is not a charity, they are one of the most profitable companies on the planet. Still, they understand the social value of making their products accessible.

Yet, I will argue that there is a bloody return on investment in accessibility.

Mobile is changing our social perception on disability and blurring the line between permanent and temporary barriers. The prevailing assumption used to be that your user will sit in front of a 14″ monitor with a keyboard, mouse and an undivided attention. But today there can be no assumptions, an app needs to be usable in many situations that impair the user in comparison to a desktop setup:

- A user will browse the web on a small, 3.5″ device with no keyboard, and only their inaccurate fat fingers as a pointing device for activating links.

- A driver will need to keep their eyes on the road and cannot interact with complex interfaces.

- A cyclist on a cold winter day will have gloves and will want to look up where they are going on a map.

- A pedestrian will look up a nearby restaurant on a sunny day with plenty of glare making it hard to read their phone’s screen.

This shouldn’t happen.

This shouldn’t happen.

The edge case of permanently impaired

users is eclipsed by the common mobile use case which needs to appeal to users with all sorts of temporal impairments: motor, visual and cognitive. Apple understands that with Siri, and Google does too with Google Now. In Firefox OS, sooner or later we will need a good voice input/output story.

I made a case for accessibility, and I could probably stop here. But I won’t. Because the real benefit of an accessible device is priceless.

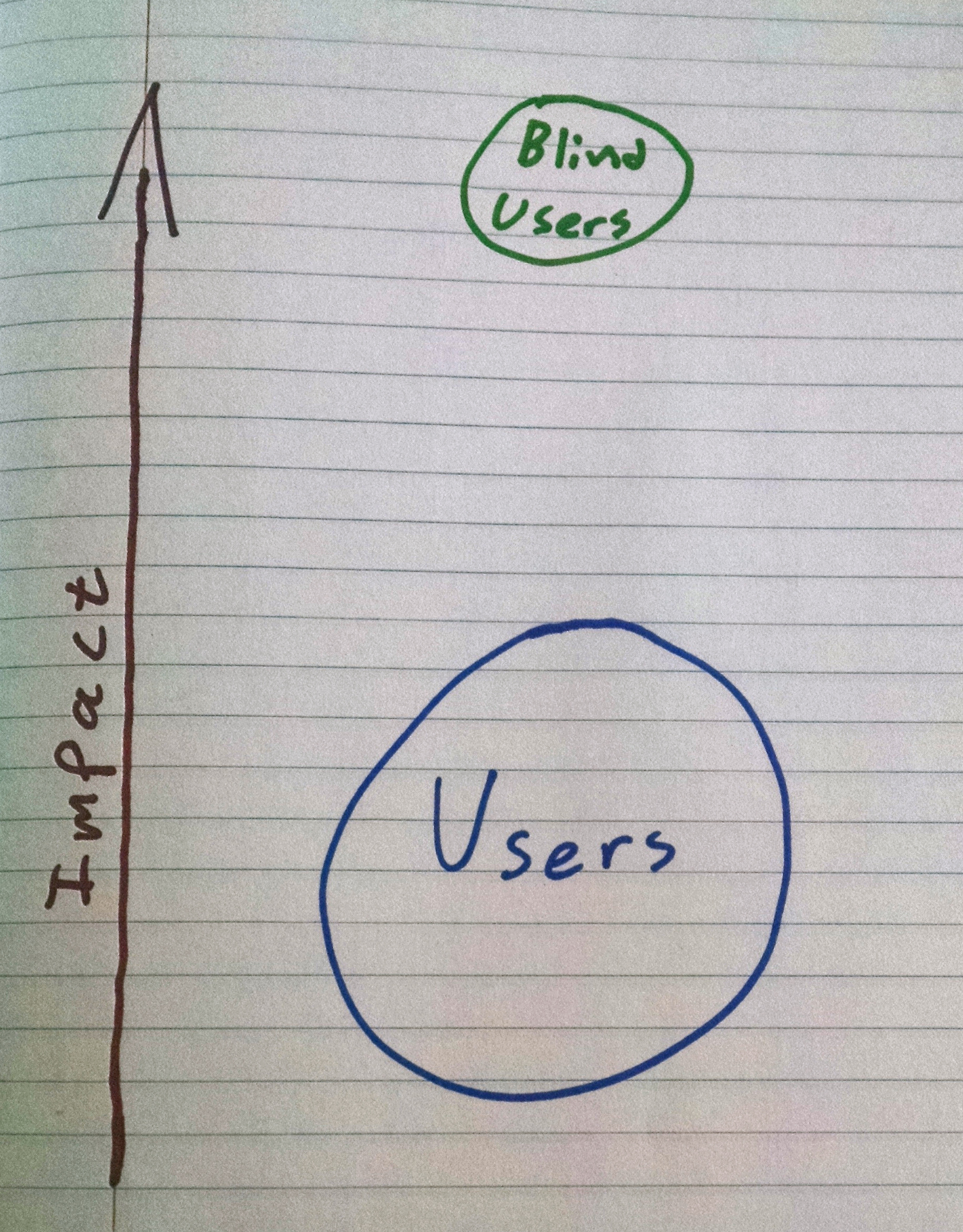

While blind smart phone users are a small fraction of the general population, the impact on their lives is so much greater.

While blind smart phone users are a small fraction of the general population, the impact on their lives is so much greater.

We all benefit from that smart phone in our pocket. The first iPhone was a real revolution. It allows us to check mail on the go, share our lives on social networks, ignore our family, and pretend like we we are doing something important in awkward parties. But for blind users, smart phones have increased their quality of life in profound and amazing ways. Blind smart phone owners are more independent, less isolated. and they can participate in online life like never before. Prior to smart phones, blind folks depended on very expensive gadgets for mobile computing. Today, a smart phone with a few handy apps could easily replace a $10,000 specialty device.

Smart phones in the hands of blind users is a very big deal.

What we need to do

To make this happen, every decision by our product team, every design from UX, and every line of code from developers needs to account for the blind user experience. This isn’t as big a deal as it sounds, screen readers support is just another thing to account for, like localization. We know today that designing and developing UI for right-to-left languages take some consideration. Especially if you live in a left-to-right world.

What we need is project-wide consciousness around accessibility. It is great that we have an accessibility team

, and I think Mozilla benefits from it. But this does not let anyone else off the hook from understanding accessibility, embedding it in our products, and embracing it as a value.

I fear that this post will disappoint because I won’t get into how blind users use smart phones, and how should developers account for the screen reader. I have written in the past about this, and Yura has some good posts on that as well. And yes, we need to step up our game, document and communicate more.

But for now, here are two things you could do to get a better picture:

- If you own an Android device or iPhone, turn on the screen reader, close your eyes and learn to use it. Challenge yourself to complete all sorts of tasks with your screen reader on. Test the screen readers limits.

- With your Firefox OS device, turn on the screen reader. It works in the same fashion as the iOS or Android one does. Check your latest creation, and see what is broken and missing.

2015 is going to be a great year for Firefox OS. I have already heard all sorts of product ideas that have the potential of greatness. We are destined to ship something amazing. But for bind users, it could be life changing.

An understated feature in desktop Firefox is the option to suppress the text and background colors that content authors choose for us, and instead go with the plain old black on white with a smattering of blue and purple links. In other words, 1994.

Why is this feature great? Because it hands control back to the user and allows people with visual impairments to tweak things just enough to make the web readable.

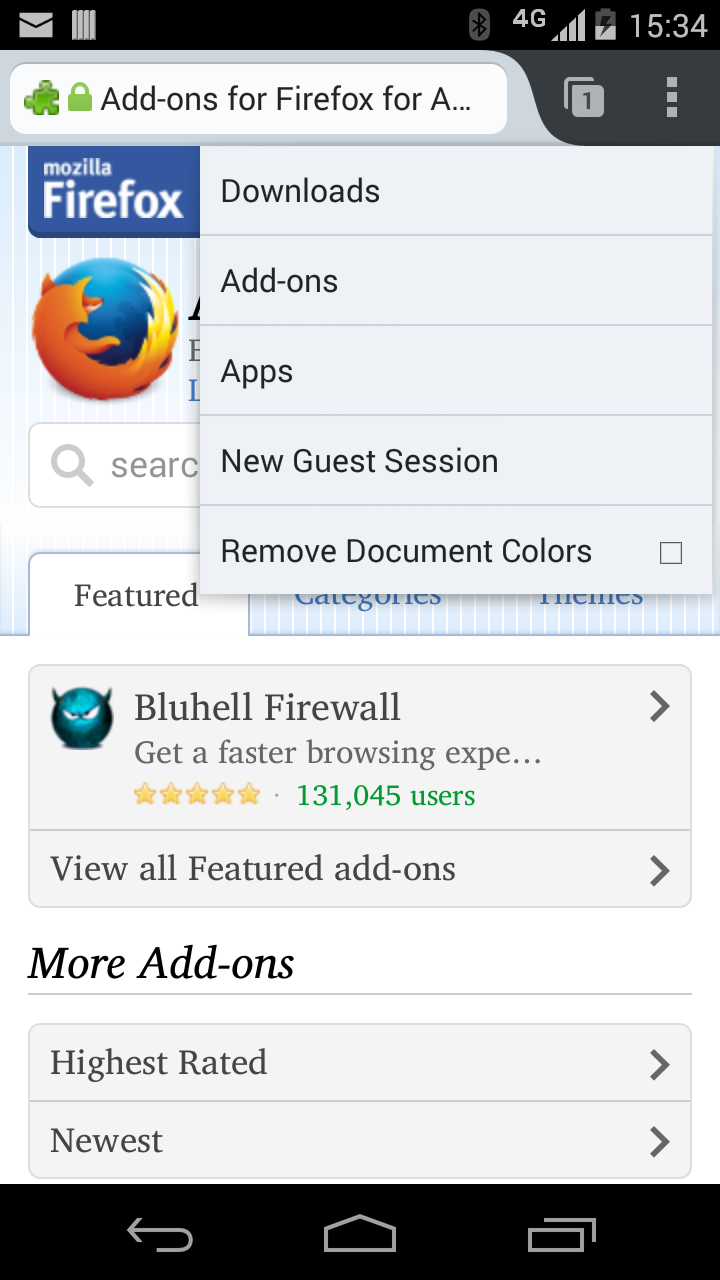

Somebody once asked on the #accessibility IRC channel why they can’t turn off content colors in Firefox for Android. So it seemed like a good idea to re-introduce that option in the form of an extension. There are a few color related addons in AMO, but I just submitted another one, and you could get it here. This is what the toggle option looks like:

[ ](/assets/uploads/2014/10/screen.png)Remove colors option in tools menu

](/assets/uploads/2014/10/screen.png)Remove colors option in tools menu

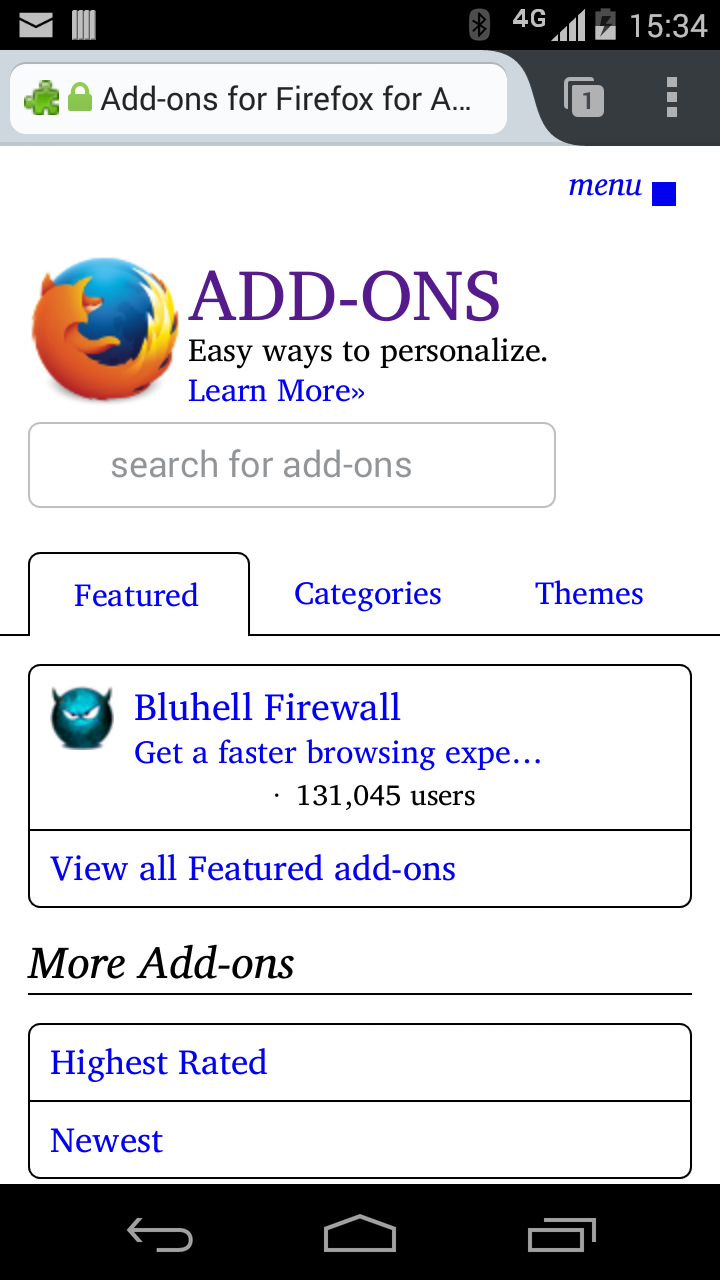

Since the color attribute was introduced, the web has evolved a lot. We really can’t go back to the, naive, monochrome days of the 90s. Many sites use background images and colors in novel ways, and use backgrounds to portray important information. Sometimes disabling page colors will really break things. So once you remove colors from AMO, you get:

[ ](/assets/uploads/2014/10/screen2.png)Okayish, eh?

](/assets/uploads/2014/10/screen2.png)Okayish, eh?

As you can see, it isn’t perfect, but it does make the text more readable to some. Having a menu item that doesn’t take too much digging to find will hopfully help folks go back and forth between the two modes and gt the best out of both worlds.